I have a friend who says he was raised an apathetic. “Apathetic” makes a pretty good description of me growing up as well. I was not an agnostic – someone convinced that God is unknowable. I had no idea if God was knowable. Maybe there was a God. Maybe not. I had never given it much thought. If there was some sort of a supreme being who spun up the world, well, we did a pretty good job of staying out of one another’s way. So I didn’t believe in God. But I didn’t disbelieve in him either. Like I say, I was an apathetic. I just didn’t care.

At some point, though, one runs into life, or life runs into us, and we start to care.

Life ran into me one summer day after sixth grade. I came home and found my parents sitting on the edge of the bed in their darkened bedroom. My mom’s hands were over her face. I could hear muffled sobs. My dad motioned me in. “Your mom and I, we have decided to separate.” And just like that, with an obviously one-sided “we,” my Leave it to Beaver life childhood was gone. My world had been nice, quiet, predictable, moneyed. Divorce tends to unravel each of those. I was no exception. It turned out that most of my friends were going through their own pain: another divorce, a mom with cancer, a dad fired, an incurable disease. A lot was pressing in on our little group that summer as we sat on the cusp of the developmental mess that is adolescence. So, as sixth grade was about to begin, I looked at the world for the first time and wondered about the pain I felt and the pain I saw.

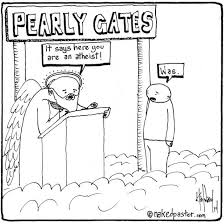

Broken people, broken families, broken neighborhoods, broken schools, broken cities, broken nations. The list of “broken” is disconcertingly long. How is it, if we are the product of a good and wise creator could the world be in such moral and physical squalor? I became an atheist for the reason many do: Pain. And just like that I was converted. I became a vocal and evangelistic atheist.

I was proud of my newfound disbelief. Make no mistake, it was much harder to be an atheist in the late 70’s. There were no Youtube videos. No Facebook memes. One had to find other atheists to talk to and go to the library and read Aldous Huxley, Bertrand Russell, and Jean Paul Sarte. And atheism wasn’t cool the way it is now. To be an atheist was not avant garde. It was oddball. Things went well, though, in my newfound unbelief.

I relished helping my Christian friends, who were ill-equipped to defend their faith, out of their unreflected upon delusions. I might have left them alone if my Christian friends had seemed happier than the rest of us. Or if there were any evidence, even the slightest, that their faith gave them the strength to live a more moral or kinder life. Unfortunately, my Christian friends tended to be the biggest partiers, the most promiscuous, and oddly, the most judgmental people in my school. Naturally I asked questions about this. “How is it that I, someone who thinks that I answer to no one but myself, live a more moral life than you, someone who will supposedly answer to an all powerful deity who smites people that do the things you do?” Their answer was remarkably unsatisfying: “You just party on Friday and Saturday and ask God to forgive you on Sunday. Christianity is pretty awesome!”

“Seriously?” I would answer. “Marx was right, faith in God is an opiate to justify whatever immoral thing you are in the mood for. More than that, it allows you to feel superior in some God-given right to stand in judgment of others. If I ever were to pick a religion, I can tell you it wouldn’t be something as lame as Christianity.”

Then there was the Bible. Picking that apart with people who don’t know it very well isn’t difficult. And don’t get me started on the weird and distasteful things the church has done (and continues to) through the centuries.

All in all, atheism worked pretty well for me. At least until the end of sophomore year in biology class…

Sophomore biology is often where churched kids begin to doubt their Christian faith. For the first time they are confronted with Darwin’s theory that time and chance account for life in all of its diversity. As the scientist said at the launching of the Hubbell telescope, “We no longer need ancient myths and foolish speculations to explain our origins.” I didn’t have the slightest inkling biology class would work in reverse for me. But it did. It was the sheep eye dissection unit the last week of school that ruined me as an atheist. The football coach / biology teacher, Mr. Swerdfeger, would sit on the front of his desk with a clear plastic bag filled with sheep eyes in one hand, reach in and grab one, and toss it the queasy students at each lab table.

Biology class had two-person tables and metal stools whose screech on the linoleum made the sound of fingernails on the chalkboard endurable. Biology lab pairs pimply, barely pubescent boys with entrancing young ladies who smell of gardens in Spring. These creatures would turn their attention toward us and inform the boys, “I will NOT touch it.” To have been spoken to by one of these goddesses was a great honor. We would have grabbed the eyeballs anyway to impress, but to have been spoken to guaranteed our obedience.

Mr. Swerdfeger pulled an eyeball from the plastic bag, and threw it toward our table in the back right corner of the class. I snatched the eyeball from the air to place in the wax tray, blackened by thirty years of use and reeking of formaldehyde. As I stared at the mass of tissue in my hand an awareness crept across my mind…There are eight or nine tissue types present in an eyeball: pupil, iris, lens, cornea, retina, optic nerve, macula, fovea, vitreous fluid. Evolution, the unit immediately preceding the dissection unit, explained that biological complexity is the result of beneficial mutation. It is the mechanism of beneficial mutation that allows life to overcome the second law of thermodynamics, which says that in the closed system of the universe, life should be running down. It is beneficial mutation that Jeff Goldblum was talking about in Jurassic Park when he famously said, “Life will always find a way.”

As I held that sheep’s eye it occurred to me that those eight or nine tissue types all have to be present and working together for the eye to be useful. Beneficial mutations are only perpetuated if there is a benefit. There is no benefit to any of those tissues without all of them present together – which should be impossible…unless someone was messing with the recipe. And it dawned on me, something, or someone had interfered in the system.

I dropped the eyeball and stood up. My worldview crumbling as my body rose from my lab stool.

Mr. Swerdfeger was annoyed at the interruption. “What’s the matter, Marino? Are you grossed out?”

“No sir.” I said, “I’m freaked out. I have to leave.” I grabbed my backpack and walked out. worldviews don’t die easily. After wandering aimlessly through the breezeways, I found myself heading home.

I did not realize it, but I had been confronted by a classic God defense: design demands a designer. By the time I walked through our back gate I knew that there must be a God and that I needed to find a religion that explained it or him or her or whatever or whoever. I was not a Christian. I was not even contemplating considering becoming a Christian. I just knew that if someone had asked me that day, “How is atheism working out for you?” My answer would have been, “It isn’t.”

I simply had a hard time believing that what I can see is all there is.

*By the way, Mr. Swerdfeger was a fantastic teacher. Once when I was in the midst of ditching two weeks of school he rode his bicycle a mile to my house with a pile of homework in his backpack and told me that if I didn’t do the hours of work to pass his class he wouldn’t just fail me, he would find me and hurt me. Mr. Swerdfeger was a large man. He finally retired when the school told him that his biology class was so difficult they were going to make it the AP course. He retired rather than dumb down his curriculum. If you ask me, every high school in the country could use a few Mr. Swerdfegers.

Oh, this is wonderful, Matt! How interesting that the adversity you experienced as a child initially engendered cynicism and rebellion, but also prepared you to recognize and acknowledge our Creator! Glory be to God! I always look forward to your thoughtful meditations.

Thank you, Elizabeth. I am going to miss you and all of the wonderful people at St. Barnabas.